Rebecca Wanzo’s new book examines a group of Black artists who explored racial caricature’s role in U.S culture.

Comics have a vexed history with racial representation. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, American political cartoons and comic strips employed caricatures that drew upon racial stereotypes. While Black superheroes occasionally appeared throughout the history of comic books, one did not lead a mainstream comic franchise until the appearances of Marvel’s Black Panther and Falcon in the late 1960s.

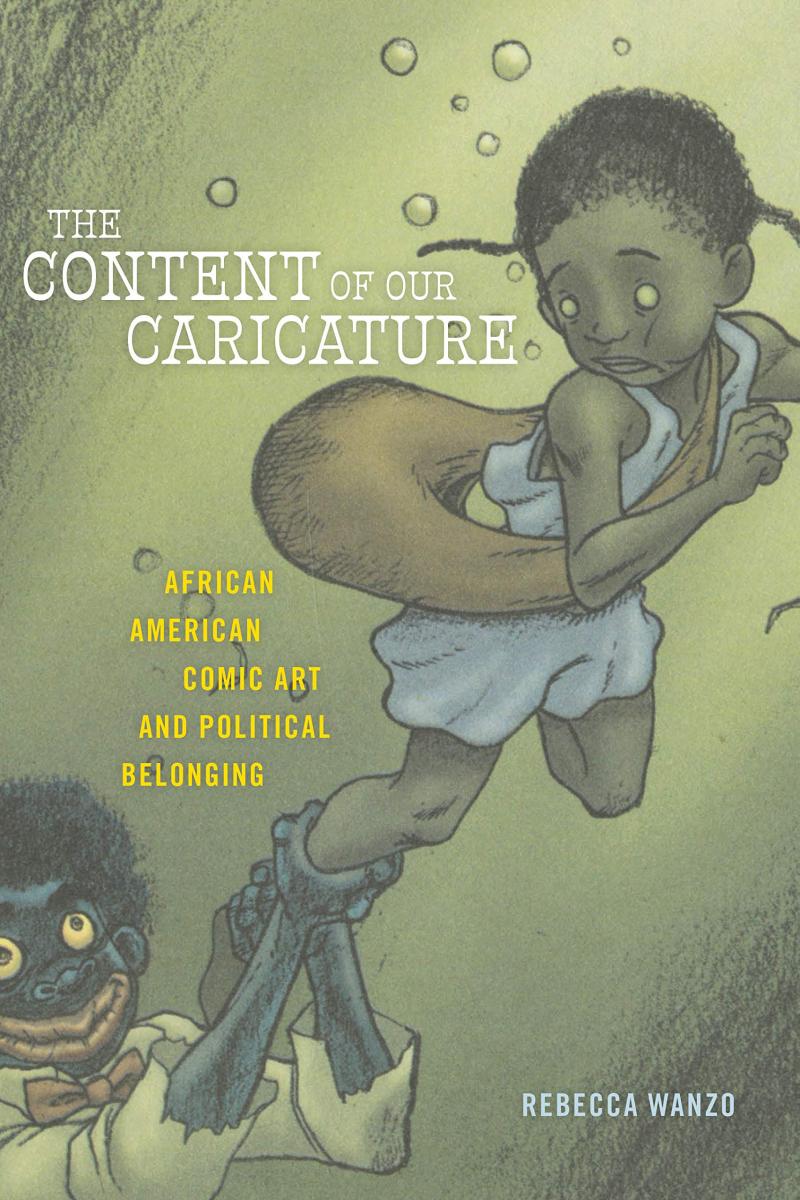

How African American cartoonists respond to the history of racial caricature is the subject of a new book by Rebecca Wanzo, professor and chair of the Department of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. She is the author of The Content of Our Caricature: African American Comic Art and Political Belonging (NYU Press), which explores the work of African American cartoonists who have made use of racist caricature as an art practice that engages with the history of slavery and racism and becomes of a means of commenting on what she terms “citizenship genres” in the United States.

Covering editorial cartoons, comic strips, underground comix, graphic biographies, and superhero comics, Wanzo writes about the works of artists such as Sam Milai, Larry Fuller, Richard “Grass” Green, Brumsic Brandon Jr., Jennifer Cruté, Aaron McGruder, Kyle Baker, Ollie Harrington, and George Herriman. These artists engage with the legacy of ugly racial stereotypes in American visual culture.

Comics remain popular not just because they are fun to read but also because they tell a story about how identity works. They have been part of our visual vocabulary in describing who belongs and who does not.

Since they rely on visual shorthand to tell their stories, comic artists frequently use both positive and negative caricatures. “We often talk about caricatures as negative stereotypes, but there are a number of caricatures that serve as ideals,” Wanzo said. “Think about how Superman and Orphan Annie are used as easy referents for ideal masculinity and innocent pluck, respectively.”

Cartoonists use such caricatures to communicate standards about belonging, community, and citizenship. In The Content of Our Caricature, Wanzo analyzes the use of what she calls “a visual grammar of citizenship” to portray both ideal and undesirable types of American citizens. Within this visual shorthand, Black characters rarely embodied the ideal. “African Americans are often treated as less than ideal or unworthy citizens,” Wanzo said, “and the artists I discuss are often exploring that theme in their work.”

The comic book artist Jeremy Love engages with that dynamic in his fantasy comic, Bayou. This series explores the legacies of racial violence and he has described it as a “Black Alice in Wonderland.” In the panel featured on the cover of Wanzo’s book, the main character of the series, a young Black girl, tries to escape from an animated golliwog doll. “The grotesque image of a golliwog doll is a racist caricature from the nineteenth century,” Wanzo said “We learn in Bayou that these grotesque-looking caricatures represent what happens to Black people who have died from racist violence and cannot let go of their bodies. They are both tragic and destructive.” The golliwog shown on the cover of Wanzo’s book is attacking a girl who has gone to the underworld to rescue her father.

The afterlife depicted in Bayou is filled with African Americans who have responded to racial violence in different ways. “In describing the Golliwog as the ‘bad thing’ that happens to your spirit if you cling to your body,” Wanzo writes, “Love suggests some agency despite victimization. In other words, monstrosity can result if racialized violence defines black subjects.”

When Wanzo first started working on this project, her publisher worried that some panels would be upsetting to readers — for example, the golliwog doll represents an ugly visual history and in this image is actively trying to hurt the little girl. But Wanzo believes there is value in sharing these images. Works like Bayou “speak about the legacy of racial caricatures that haunt us and can injure us. In the hands of Black artists, that visual iconography can also do critical work in addressing this history and pushing us to think in more complex ways about how those lingering images interact with our attempts move forward toward more just futures.”

Comics have often depicted an ideal form of citizenship that African Americans “cannot fully embody or make their own,” Wanzo writes. “The Black caricature stands in place of real Black citizenship, with the ideal figuratively but not realistically in reach.”

Some comic artists have tried to move past the medium’s history of violent imagery without grappling with the ramifications of that legacy. The result is often figures like Charles Schultz’s Franklin, the first Black character in Peanuts who was so perfect a person as to be almost devoid of any character at all. “Even with good intentions,” Wanzo said, “inclusion without complexity can be another way of denying the humanity of people.”

Black comic artists use that double-bind to provoke visceral responses from readers. Shying away from the language of caricature robs Black characters of their identity and citizenship, and so Black comic artists grapple with the legacy of caricature head-on. Some artists employ racial caricature in their work to comment on the violence these images enact. Others question the idea that these images are dangerous at all or even call into question forms of activist art that they find counterproductive. “The reality is that we are haunted by these ugly representational histories,” Wanzo said.

The Content of Our Caricature describes a revolutionary artistic practice that urges readers to face the violence of a shared visual language. The only way forward, Wanzo suggests, is to develop a more nuanced relationship with the past.

Read more about The Content of Our Caricature at the New York University Press website.