A new StudioLab graduate course explores trauma and memory in community spaces beyond campus.

To understand how communities memorialize the trauma of systemic racial violence, researchers need to work in those communities, according to Anika Walke and Geoff K. Ward. In the “Memory for the Future” StudioLab class, held in the Lewis Collaborative, Walke, associate professor of history, and Ward, professor of African and African-American studies and director of the WashU & Slavey Project, ask graduate students to forget about the standard graduate seminar research paper. Instead, their students partner with local organizations to develop projects that benefit the community. The projects aim to participate and intervene in current debates about the possibility of repair and forms of memory and commemoration that address ongoing inequalities and injustice. Walke and Ward are partnering with a number of community organizations for the course, including the St. Louis Kaplan Feldman Holocaust Museum, the Griot Museum of Black History and Culture, the George B. Vashon Museum, the Reparative Justice Coalition, the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Special Collections in Olin Library, and CounterPublic.

“How do we commemorate the victims of racialized violence in the past while also educating the public about the dynamics and contingencies of atrocities against particular social groups?,” Walke asked. “Our class offers a framework to think critically about memorial practices and, during the practicum, put these insights to work to facilitate change.” The StudioLab leverages the concept of multidirectional memory, developed by scholar Michael Rothberg in a book of the same title, to develop new forms of humanities education and practical public history. The concept emphasizes the productive relationship between different, yet related histories and legacies of violence such as the Holocaust, slavery, apartheid, and colonialism that emerges if and when they confront each other in the public sphere.

Students engage with these questions of trauma and memory in St. Louis and, thanks to a grant from the Feldman Education Institute, also in Tulsa, Oklahoma. A study trip in September allowed the students to learn how another city, that deals with a very similar history of racialized violence as St. Louis, has responded to this history, and draw on this experience in developing their own community-based projects.

St. Louis is the intersection point of a number of histories of racial violence. The city was built on territories once settled by the Missouri and Osage tribes, and it was the site of a number of lynchings. The World Exhibition of 1904 put the colonial and imperialist aspirations of the city on display. White mobs killed up to 150 African Americans in East St. Louis in 1917, and in the 1950s white supremacists marched through the streets of St. Louis. After World War II, many Holocaust survivors settled here, as did many Bosnian refugees in the 1990s in the aftermath of the genocide and war in the former Yugoslavia.

“We're constantly faced with these atrocities in the past; they continue to shape our contemporary society. Our task as public scholars is to make those histories plain, visible, and available while also marking them as something that we need to recognize as having produced injury and suffering that we cannot just leave behind us,” Walke said.

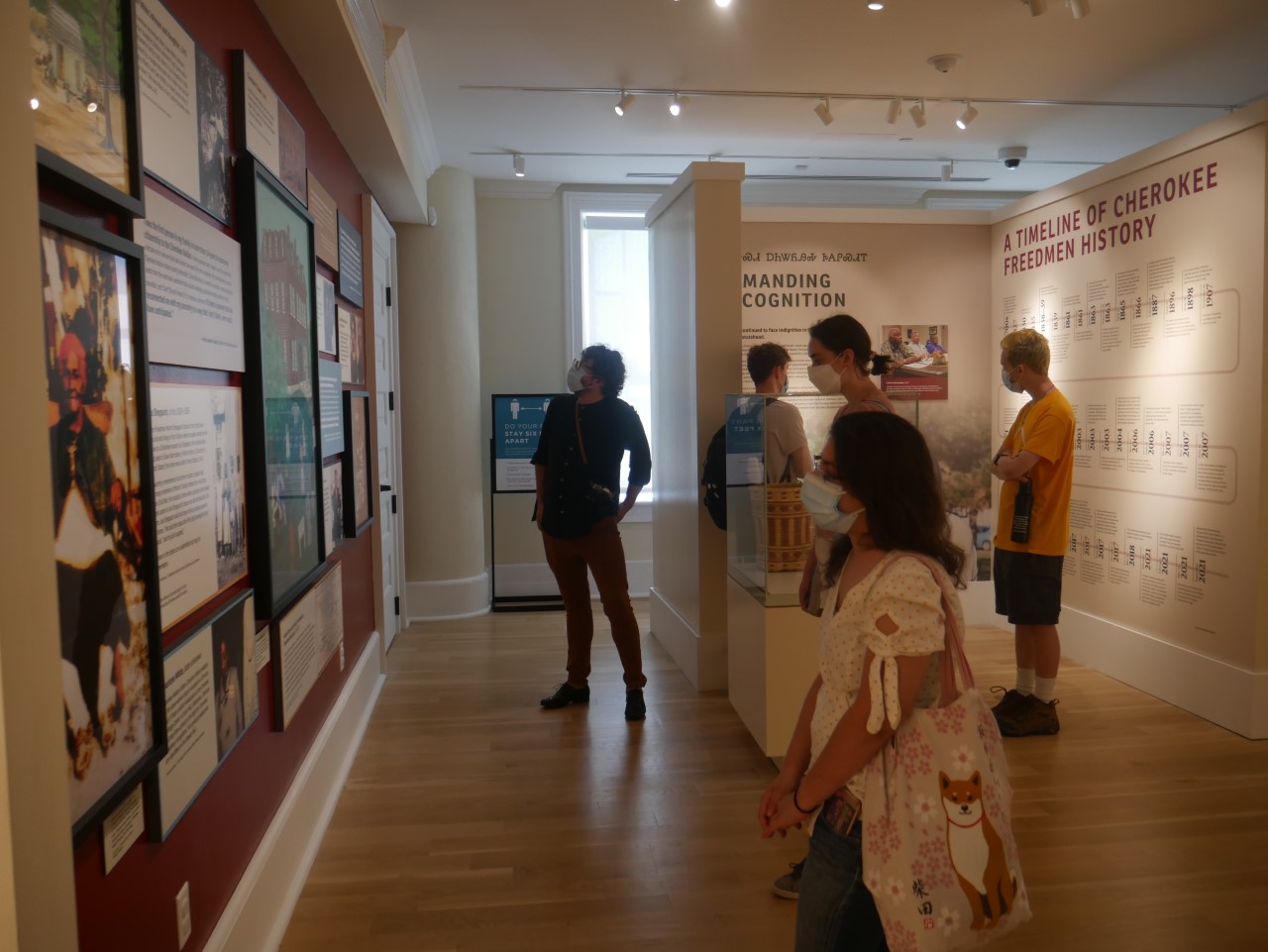

In September, Ward, Walke, and postdoctoral fellow Santiago Rozo Sánchez traveled with students from the course to Tulsa, Oklahoma, where they visited the city’s memorials to victims of systemic racial violence including the Greenwood Cultural Center, Greenwood Rising, and the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park. They also traveled to the the Sherwin Miller Museum of Jewish Art, and the Cherokee National History Museum in Tahlequah, OK, about an hour east of Tulsa.

“Like St. Louis, Tulsa is another wounded place shaped by histories of colonialism and slavery,” Ward said. “Tulsa is in the process of grappling with those histories and their legacies through the creation of interpretive centers and reparative park spaces alongside museum exhibits.”

Walke and Ward’s students will complete their practicum, with projects including everything from helping local schools develop teacher training modules about systematic racial violence to working with the St. Louis Kaplan Feldman Holocaust Museum on public programming, by the end of the academic year. Several students entered the course having existing partnerships with community organizations. Nkemjika Emenike is writing a preservation plan for the Washington Park Cemetery Foundation, helping to restore a historic African American cemetery located in Berkeley, Missouri.

The StudioLab course is part of the Center for the Humanities’ Redefining Doctoral Education initiative, which helps equip doctoral students in the humanities with professional skills beyond teaching and research. Walke and Ward note that students have had to think both about the academic theory involved in studying trauma and memory and learn how to manage complex community-engagement projects. Even the course itself, held inside the newly renovated Lewis Collaborative building, embodies the spirit of community collaboration. Class sessions are held in a public space behind a coffee shop, and Walke and Ward invite members of the public to join discussions while they have a latte once the coffeeshop is open.

Ward says that public engagement remains the most challenging aspect of the course.

“It’s not specifically academic,” he explained. “Some students are finding it challenging to be comfortable with uncertainty, but we want them to be uncomfortable to a certain degree. That will really prepare them to do the kind of work that the world will actually demand of them, to take chances and work together with people you don’t know to achieve something for the community.”